Translating Sonic Languages: Different Perspectives On Music Analysis

For this guest post we are glad to share Benjamin Doubali’s analysis on how to visualize sound. Benjamin studied sociology in Mainz and Paris. Through his work and research, he aims at exploring shifts in society, knowledge and everyday interactions under the conditions of digitalization. He is passionate about artistic concepts in regards of the relationship between culture and technology.

The article was written by Benjamin Doubali.

Let’s say music is a code.

This call may seem a little confusing. Isn’t music an aesthetic experience, isn’t it dynamic, fleeting? Isn’t it everything that code usually cannot be? Sure, music is unique, it is art. Nevertheless, allow that thought for a moment: music is systematically structured, categorised, it follows a strict “grammar”. It is not mysterious, but enigmatic. Music is auditory code. A code that needs to be deciphered and translated. And we can process this code by technological means, like any other sign system. Unlike other codes, however, the code of music is not stable and predictable, but surprising and diverse.

Songwriters are translators – and so are music lovers

Consider the matter from the songwriter’s point of view: she has an experience to share, a story to tell or a musical idea she can’t let go of. Songwriters seek to express feelings from the depths of the human experience, like the confusion after a break-up, missing the person that is now just somebody you used to know. They have the knowledge and the tools (literally “instruments”) to transform and condense ideas into sound. For this purpose, they use established symbol systems, tonal grammar, musical code. A songwriter expresses her feelings in a sonic language, which is a term used by the musician Claudio in addressing this issue. The songwriter becomes the translator of her own emotional world.

Later, someone will hear the sonic language, its tones, rhythms, lyrics and translate it once again, perhaps feel something, associate situations, or images with it. How does emotion translate into a great song? And how does it “turn back”?

Admittedly, this is a very broad concept of translation: I refer to the mere interpretive, consistent transmission from one thing to another. One could call it intersemiotic translation; this is a term from philology, the cultural study of languages, indicating the translation between totally different sign systems (or modes of expression). This is what happens, for example, when novels are adapted for cinema.

Sounds are symbols – and they’re able to touch us

How does a great song turn into emotion? It’s not so easy to determine: Sound does not “carry” meaning in some magical way. In other words, the emotion, and images we associate with an auditory impression are not surfing on the sound waves, they’re not transported to us. Sound itself is a meaningless symbol of a complex code. The solution can be found elsewhere: Emotion has not been transmitted into our consciousness – it is already there.

Music can resonate in places of our inner world; it touches and moves us. By listening to music, we feel sadness, joy, and ecstasy – fundamental components of the human experience. These are not plainly inscribed in the sonic language. We should rather think of music as a way to stimulate impressions which are deeply intertwined with our existence.

David Anderson © Unsplash

When music looks like twisting shapes

Our interpretations of the sonic language encompass elusive associations, slight toe tapping, wild dancing, and unrestrained singing. Another unique mode of musical perception is called synaesthesia. Synaesthesia is a cognitive phenomenon, describing involuntary combinations of perception. In a common form of synaesthesia, people perceive numbers as inherently coloured. For others, sounds have shapes. Illustrating this, a synesthete described an example to me: When two people sing together, she perceives two lines that either run harmoniously or repel each other. The cognitive perception of music can thus become a dance of geometric forms.

Su-san Lee © Unsplash

This is fascinating and underlines that the full meaning of the sonic language isn’t part of the physical sound, but only evolves through individual perceptual processing of its structures, sometimes creating surprising effects. The listener’s perception processes the material entity of sound into an experience. According to this, a melody is like a sequence of data that requires a “processing unit” to be meaningful (for more on this, I recommend the book “Muster” by the sociologist Armin Nassehi).

Using digital technology for translation

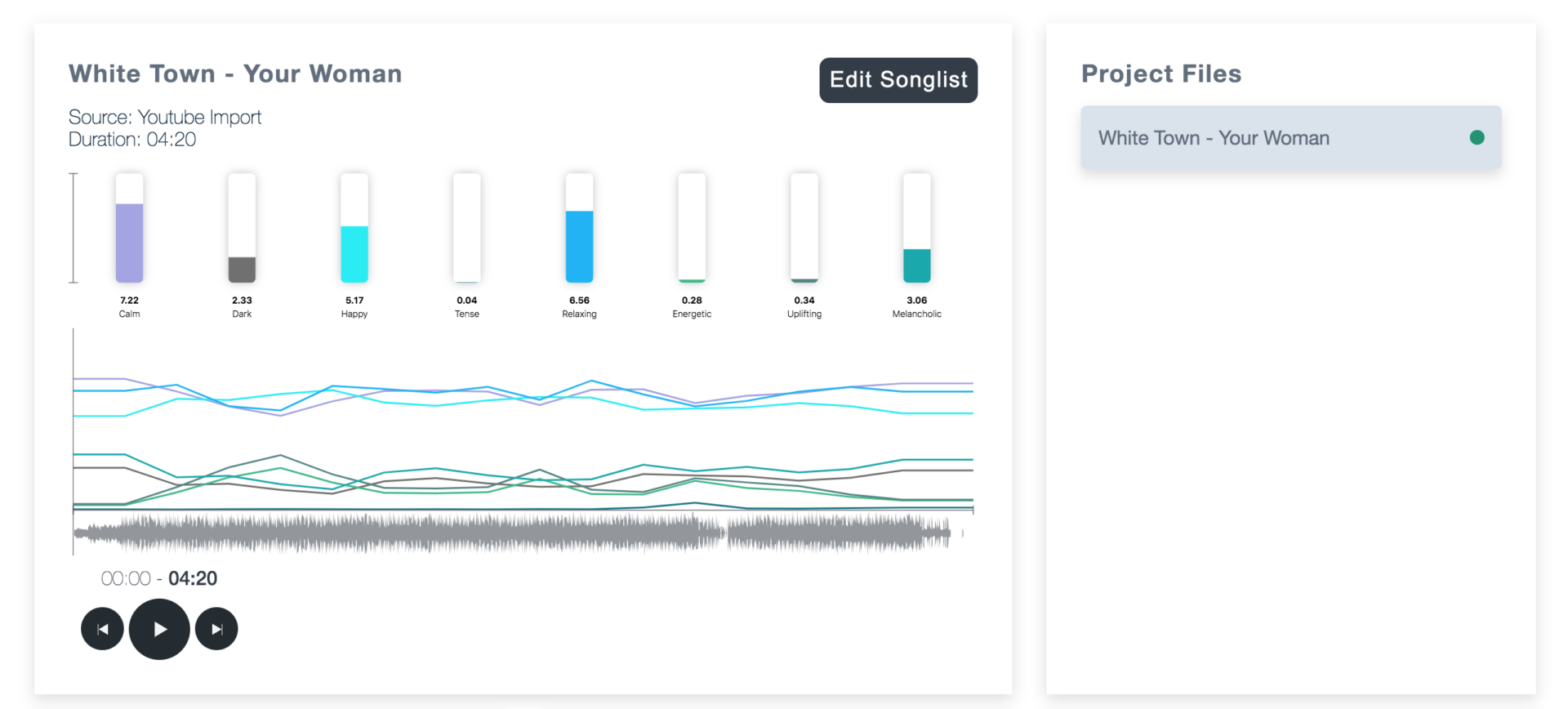

It may hardly come as a surprise that the power to process and therefore translate the sonic language is not an exclusively human ability. Digital technology can also access the sonic language. Cyanite’s AI is trained to analyse it by recognising recurrent patterns.

The process to successfully analyse music with neural networks takes several steps. Following my reasoning, we can picture these steps as translatory tasks. When it comes to data pre-processing, the team at Cyanite generates a visual representation of music (namely spectrograms); an activity we can call a “strategic rearrangement” of music: The characteristics of music are translated into graphical patterns, which can therefore be subject to pattern recognition. With the help of strategic rearrangements, the musical code reveals itself. After thorough training procedures, the AI learns to “read” the sonic language and to ascribe, how it resonates in us.

Going a step further: Creative Coding

It is well known that there are bittersweet ambiguities in music; a song can be both uplifting and sad. Cyanite’s music analysis tries to do justice to such contingencies by giving probability values for its attributions and by allowing “overlapping” mood categories.

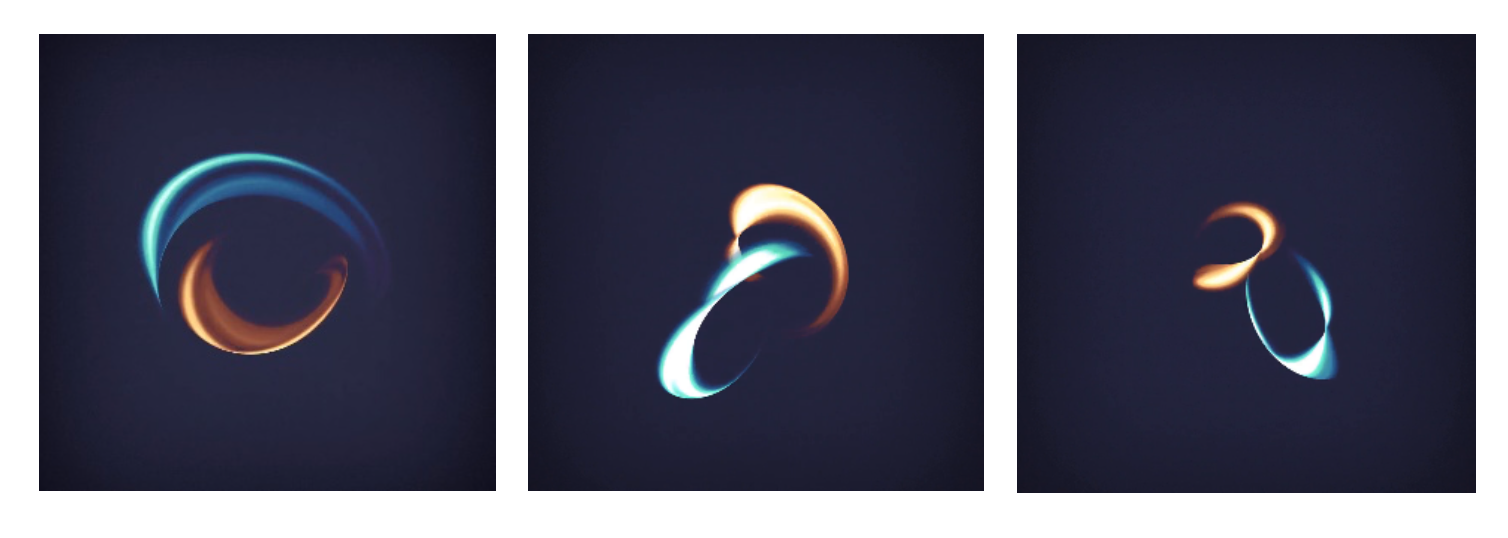

In the context of inherent ambiguities, the independent art project vi · son tries a different, creative approach to digitally translate music. The project is working on audio-reactive digital art and engages with the question: Can we make music visible? Not just metaphorically, but truly?

To translate the sonic language visually, the group applies methods of creative coding. Particularly so-called Generative Art enables data-based artworks such as moving sound sculptures that accentuate specific features of music. The curator and digital art expert Jason Bailey writes: “Generative Art is art programmed using a computer that intentionally introduces randomness as part of its creation process.” This doesn’t imply the complete autonomy of the machine nor total command over it: “The truth is that generative artists skillfully control both the magnitude and the locations of randomness introduced into the artwork.” Generative Art is a way to explore portrayals of sound-data, creating visual suitable representations of music. The resulting artworks interpret and reflect the spirit and aesthetics of the sonic language.

Guido Schmidt & vi · son: Sound Data Sculpture Sketch

One example is the digital scene “aurora” from the series Sound Data Sculpture Sketches. The creation process starts with a set of dots that move on a sphere. Over time their path is traced to form tubes, this produces an organic appearance. A representation of the underlying song’s frequencies is texture-mapped onto the geometry of the tubes and used to generate colour gradients that react to music. From this interpretative, digitally mediated translation of the original song, a dreamy audio-sculpture is created. By interpreting the musical parameters, this artwork goes further than a mere technical analysis. It thereby contemplates the poetry and beauty of the sonic language, seeking to visually formulate an accurate translation.

The project presents further examples of creative music visualizations in an ongoing digital exhibition.

The whole theme of “translation” points to the fact, that music is socially formalised and follows symbolic structures. Music is deeply connected to our human experience because it works like a language, because it translates into emotion and bodily reactions. The notion that music is tangible and rests upon patterns that we can calculate and process with digital technologies is not as weird or scary as it might seems. Music is a code – and that is a beautiful thing.

Visit vi · son ‘s digital exhibition here

For more of our blog articles,

we recommend to check these out:

3 Ways to Display and Integrate AI Search Results in Your Music Platform

The 4 essential Steps for analyzing Music with Neural Networks